U.S. President Barack Obama has warned that no amount of U.S. firepower could keep Iraq together if its political leaders did not disdain sectarianism and work to unite the country.

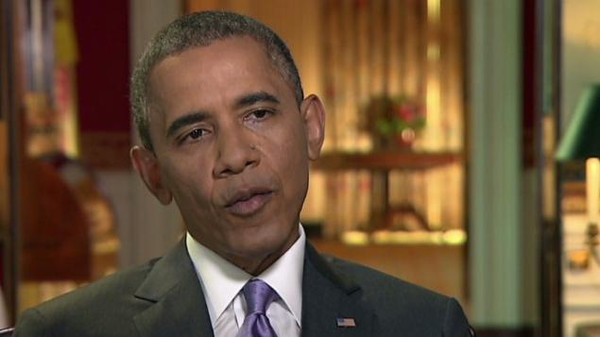

Obama told CNN Friday, a day after announcing the dispatch of 300 special forces advisors to Iraq following a lightning advance by extreme Sunni radicals, that American sacrifices had given Iraq a chance at a stable democracy, but it had been squandered.

“There’s no amount of American firepower that’s going to be able to hold the country together,” Obama said in an interview.

“I made that very clear to [Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-] Maliki and all of the other leadership inside of Iraq.”

“We gave Iraq the chance to have an inclusive democracy. To work across sectarian lines to provide a better future for their children. And unfortunately what we’ve seen is a breakdown of trust,” Obama said.

Washington has pointedly declined to endorse Prime Minister al-Maliki, a Shiite, who is blamed here for failing to reach out to the Sunni community in the two-and-a-half years since US troops left, thus laying the conditions for the current crisis.

Obama is warning that only a new effort to frame an “inclusive” political system by Iraqi leaders will keep the country together and repel the challenge from Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) fighters who have seized several key cities in Iraq, including Mosul.

Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, the most respected voice for Iraq’s Shiite majority, also mounted pressure on Maliki to seek an exit to the crisis via a political solution.

He called on Maliki to form an inclusive government or step aside.

His thinly veiled reproach was the most influential to place blame on the Shiite prime minister for the nation’s spiraling crisis.

The focus on the need to replace Maliki comes as Iraq faces its worst crisis since the withdrawal of U.S. troops in 2011.

Over the past two weeks, Iraq has lost a big chunk of the north to the Al-Qaeda-inspired Sunni militants of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, whose lightning offensive led to the capture of Mosul, the nation’s second-largest city.

The gravity of the crisis has forced the usually reclusive al-Sistani, who normally stays above the political fray, to wade into politics, and his comments, delivered through a representative, could ultimately seal Maliki’s fate.

Calling for a dialogue between the political coalitions that won seats in the April 30 parliamentary election, Sistani said it was imperative that they form “an effective government that enjoys broad national support, avoids past mistakes and opens new horizons toward a better future for all Iraqis.”

Deeply revered by Iraq’s majority Shiites, Sistani’s critical words could force Maliki, who emerged from relative obscurity in 2006 to lead the country, to step down.

On Thursday, Obama stopped short of calling for al-Maliki to resign, but his carefully worded comments did all but that. “Only leaders that can govern with an inclusive agenda are going to be able to truly bring the Iraqi people together and help them through this crisis,” Obama declared at the White House.

The Iranian-born Sistani, believed to be 86, lives in the Shiite holy city of Najaf, south of Baghdad, where he rarely ventures out of his modest house on a narrow alley near the city’s Imam Ali shrine and does not give media interviews.

The extent of al-Sistani’s influence was manifested in the years following the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq when he forced Washington to modify its blueprint for the country and agree to the election of a constituent assembly that drafted the nation’s constitution.

For the past two years, he has shunned politicians of all sects, refusing to receive any of them to show his disillusionment with the way they run the country. However, the danger posed by the Islamic State militants appears to have forced him to say more.

His call to arms has given the fight against the Sunni insurgents the feel of a religious war between Shiites and Sunnis. His office in Najaf dismissed that charge, with his representative, Ahmed al-Safi, saying Friday: “The call for volunteers targeted Iraqis from all groups and sects. … It did not have a sectarian basis and cannot be.”

Al-Maliki’s State of Law bloc won the most seats in the April vote, but his hopes to retain his job are in doubt with rivals challenging him from within the broader Shiite alliance. In order to govern, his bloc must first form a majority coalition in the new 328-seat legislature, which must meet by June 30.

If al-Maliki were to relinquish his post now, according to the constitution the president, Jalal Talabani, a Kurd, would assume the job until a new prime minister is elected. But the ailing Talabani has been in Germany for treatment since 2012, so his deputy, Khudeir al-Khuzaie, a Shiite, would step in for him.

Al-Maliki’s Shiite-led government long has faced criticism of discriminating against Iraq’s Sunni and Kurdish populations. But it is his perceived marginalization of the once-dominant Sunnis that sparked violence reminiscent of Iraq’s darkest years of sectarian warfare in 2006 and 2007.

Shiite politicians familiar with the secretive efforts to remove al-Maliki said two names mentioned as replacements are former vice president Adel Abdul-Mahdi, a Shiite and French-educated economist, and Ayad Allawi, a secular Shiite who served as Iraq’s first prime minister after Saddam Hussein’s ouster. Others include Ahmad Chalabi, a one-time Washington favorite to lead Iraq, and Bayan Jabr, another Shiite who served as finance and interior minister under al-Maliki.

Nearly three years after he heralded the end of America’s war in Iraq, Obama announced Thursday he was deploying up to 300 military advisers to help quell the insurgency. They join some 275 troops in and around Iraq to provide security and support for the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad and other American interests.

But the U.S. leader was adamant that U.S. troops would not be returning to combat.

Obama has held off approving the airstrikes sought by the Iraqi government, though he says he could still approve “targeted and precise” strikes if the situation required it and if U.S. intelligence gathering identified potential targets.

Manned and unmanned U.S. aircraft are now flying over Iraq 24 hours a day on intelligence missions, U.S. officials say.

A Shiite politician close to Maliki said Obama did not offer enough to help Iraq at its hour of need.

“His plan does not rise up to the level of Iraqi-U.S. relations. His message is clear: America is not ready to fight terrorism,” said the official, speaking to The Associated Press on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the subject.

Another Shiite, cleric Nassir al-Saedi, warned that the 300 advisers would be attacked. Al-Saedi is loyal to anti-U.S. cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, whose Mahdi Army militia fought the Americans during their eight-year presence in Iraq.