India’s main opposition party, tipped to form the next government, appears to be returning to its Hindu nationalist roots at the start of a five-week general election, raking up divisive issues and using strong language in an area hit by religious riots.

India’s main opposition party, tipped to form the next government, appears to be returning to its Hindu nationalist roots at the start of a five-week general election, raking up divisive issues and using strong language in an area hit by religious riots.

Criss-crossing the country for months before the first phase of voting began on Monday, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its candidate for prime minister, Narendra Modi, had mainly campaigned on a ticket of better governance, economic development and job creation.

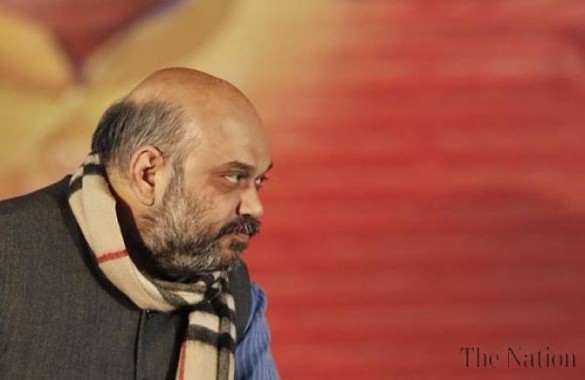

But just hours after voting started, the election commission demanded an explanation from Modi’s chief aide Amit Shah, accusing him of incendiary speeches in towns where dozens of people, mostly Muslims, were killed in Hindu-Muslim riots last year.

“It is not anyone’s hobby to riot. When justice is not done to all the parties and the action is one-sided action, then the public is forced to come out in the streets,” Shah said in the town of Muzaffarnagar in Uttar Pradesh state last week, according to a transcript provided by the commission.

In a series of speeches in the area, Shah also said voters should reject parties that put up Muslim candidates. He said Muslims in the area had raped, killed and humiliated Hindus. Shah did not respond to requests for comment, but the BJP has said he was within his rights to ask people to express their anger through the ballot box.

India’s 1.2 billion people include 150 million Muslims, who form a sizeable minority in Uttar Pradesh, the country’s most populous state and a key electoral battleground. The riots in Muzaffarnagar last year started with a minor scuffle, which were exacerbated by inflammatory speeches by several local politicians, news reports have said.

Although sectarian rioting is on the decline in India, it is still hit by spasms of Hindu-Muslim violence. Hundreds of thousands of people were killed when colonial India was divided in 1947 into Hindu-majority India and Pakistan, an Islamic state. Elections in India are also times of heightened tensions because political parties often pitch for votes on the basis of religious identity.

On Monday, the BJP released its election manifesto, promising to build a temple on the site of a mosque torn down by Hindu zealots more than two decades ago, reopening one of the most divisive issues in the country. The party also said it remained committed to withdrawing the special autonomous status for Jammu and Kashmir, India’s only Muslim-majority state.

Opinion polls have said Modi is favourite to form the next government after results are announced on May 16, thanks to a strong campaign highlighting his economic competence in running the western state of Gujarat for 13 years.

But critics say he has a darker side and accuse him of failing to stop the killing of Muslims in riots in Gujarat in 2002. Modi has denied the accusations and the Supreme Court has said there is not enough evidence to prosecute him.

A survey released by respected pollsters CSDS last week showed the BJP and its allies winning the largest number of seats but falling short of a majority. The decision to play on religious sentiments may be a last-minute attempt to woo some blocs of Hindu voters, analysts said.

The BJP maintains it is campaigning on economic issues and a vow to end what it says is deep-rooted corruption in the government headed by the ruling Congress party.

Shah is a controversial figure, who was charged in 2010 with the extra-judicial killing of Muslims accused of terrorism when he was the interior minister in Gujarat. He denies the charges and is free on bail.

The BJP has said the charges are trumped up at the behest of the Congress party and he is expected to hold a senior government position if Modi becomes prime minister. In the sugarcane fields and streets around Muzaffarnagar, the scene of the riots last year, Hindu students, labourers and workers said they would vote for Modi.

“We are treated like second-grade citizens in our own homeland because most political parties and their leaders are running after the Muslim vote. That is why I wish to support Modi this time, we have a lot of hope for him,” said Virender Malik, a labourer in a sugarcane field.

About 50,000 people, mainly Muslims, were driven from their homes in the rioting in Muzaffarnagar. Some are still living in squalid relief camps, where support is strong for the state government run by the Samajwadi Party, which is backed by Muslims because of its staunch opposition to the BJP.

“We are all for the Samajwadi Party which is our only hope against the BJP because of whom we got driven like mules away from our homes,” said Naseemuddin, a 55-year old Muslim farm labourer.

The BJP, until then on the periphery of national politics, burst into prominence in the late 1980s as it helped mobilise a movement leading to the destruction of a 16th-century mosque in the Uttar Pradesh town of Ayodhya that Hindus claimed was built on the birthplace of the god-king Ram. About 2,000 people were killed in riots across India in 1992 after the disputed mosque was torn down by Hindu mobs.

Many of the party’s core supporters want to build a temple at the site, a move supported in the manifesto unveiled on Monday.

“Once we have a Modi government in place, I am sure the grand Ram temple in Ayodhya will become a reality. We have been waiting long enough for that,” said Sharad Sharma, an activist with a right-wing nationalist group in Ayodhya.

Also in the manifesto were promises to protect and promote cows, which many Hindus consider sacred. The issue is close to the heart of supporters of Hindutva, a brand of Hindu nationalism.

The decision to put provisions such as the construction of the Ram temple in the manifesto was taken mainly to satisfy hardliners in the party, one person involved in drafting the document said.

“You have to put it in there, so you do,” he said.

E. Sridharan, a political scientist at the Pennsylvania Center for Advanced Study of India, said the polarised atmosphere and such pledges could help shore up support in Uttar Pradesh, which elects 80 of the 543 lawmakers sent to the lower house of parliament.

The BJP has said it aims to win up to 50 seats in the state, from just 10 at the last election in 2009.

“I think maybe on the ground in some states, Uttar Pradesh in particular, they need to add a flavour of this to their campaign to mobilise Hindutva votes,” said Sridharan.