The core of a giant Nasa rocket that will return astronauts to the Moon has undergone a crucial test.

For the first time, engineers fully loaded a core stage of the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket with super-cold liquid propellant, controlled it and then drained the tanks.

That propellant is fuel and an oxidiser – a chemical that makes the fuel burn.

Engineers wanted to check things worked as expected before the SLS makes its maiden flight in about a year’s time.

It was part of a testing programme known as the Green Run, that is being carried out at Nasa’s Stennis Space Center, near Bay St Louis in Mississippi.

This evaluation, known as the wet dress rehearsal (WDR), was the seventh of eight tests on the core stage. Nasa said the rocket responded well to the propellant being loaded. But the test experienced an unexpected shutdown a few minutes earlier than was planned.

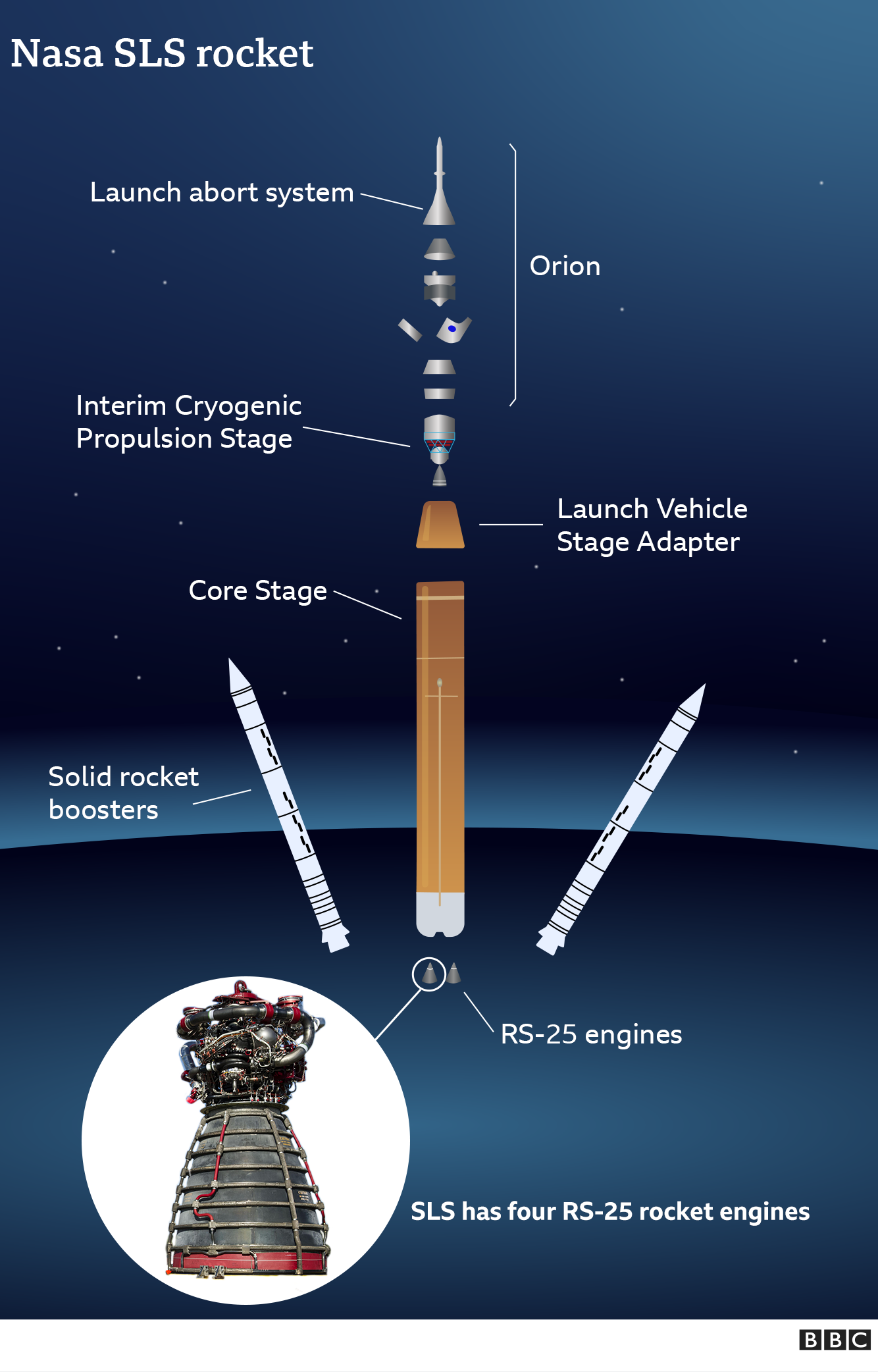

However, the completion of the WDR should set up the eighth and final test – a “hotfire” – where all four RS-25 engines at the base of the core will be fired together for the first time.

This very rocket segment will loft the first mission in Nasa’s Moon exploration plan – known as Artemis. This mission, which has been scheduled for November 2021, will send the next-generation Orion spacecraft on a loop around Earth’s only natural satellite.

There will be no crew aboard for this test flight. But the third Artemis mission, in 2024, will land the first humans on the lunar surface since the Apollo 17 mission in 1972.

The Green Run helps ensure any issues are ironed out before the complex rocket segment is transported to Florida to prepare it for launch.

Over the course of several hours, engineers at Stennis loaded the core stage with more than 700,000 gallons (roughly 2.6 million litres) of liquid hydrogen and oxygen.

“This is an incredibly exciting time,” said Jim Maser, senior vice-president at Aerojet Rocketdyne, which builds the RS-25 engines. “We’re really getting to some of the most significant aspects of the testing programme.”

The rocket section is anchored to a giant steel structure called the B-2 test stand, which was once used to test engines for the massive Saturn V rocket that carried astronauts to the Moon in the 1960s and 70s.

The propellant was brought to the site on six barges via the waterway that winds through the grounds of Stennis Space Center.

The barges were moored near the test stand while the super-cold (cryogenic) propellants aboard were piped into the core stage.

Hydrogen and oxygen are gaseous at room temperature, but gases take up lots of space. Turning them into liquids allows an equivalent amount to be stored in a smaller tank.

This requires the hydrogen fuel to be cooled to minus 253C (minus 423F) and the oxygen (the fuel’s oxidiser) to minus 183C (minus 297F).

After being filled, the tanks needed to be topped up – replenished – continually because liquids at such low temperatures boil off over time.

During the test, liquids were due to flow through the turbopumps – which feed propellant to the engine combustion chambers – and the engines themselves. This helps prepare the systems to be started.

It is all designed to mimic as closely as possible what would happen in the hours prior to a real flight. “We’re just trying to get as much data as we can so that, on the next run, we get further. And we want to find anything that could be improved during this wet dress to prepare for hotfire,” Ryan McKibben, Green Run test conductor for Nasa, told BBC News.

On its Artemis blog, Nasa said: “First looks at the data indicate the stage performed well during the propellant loading and replenish process.”

While all this was happening, teams from Nasa and Boeing – the prime contractor for the SLS – carried out a simulated launch countdown. They were due to take the count all the way to the T-minus (time remaining) 33 seconds point.

But Nasa said the test ended a few minutes short of the planned countdown duration. Teams are evaluating the data to pinpoint the exact cause of the early shutdown.

Speaking in October, John Shannon, vice president and SLS programme manager at Boeing, explained: “We’ll spend about two weeks looking at the data to make sure all the systems behaved as expected.

“We’ll go out and inspect the vehicle, make sure there are no surprises.”