There are growing concerns for the wellbeing of a British man facing up to three years in jail for taking down a Pakistani flag from a public square in Pakistani-administered Kashmir.

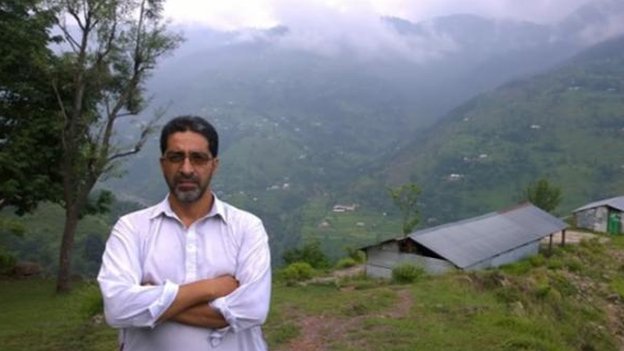

Tanveer Ahmed Rafique, a 48-year-old activist who has called for the disputed region to be granted independence from both Pakistan and India, was detained in August in the city of Dadyal. His wife told the BBC he has held a number of hunger strikes in protest at being denied bail and had become “extremely weak”.

Fareezam Rajput said she believes Pakistan’s intelligence agencies are pressuring the courts to continue to keep her husband in detention.

Police files show Mr Rafique has been accused of “unauthorisedly removing the National Flag of Pakistan”. Officials in Pakistani-administered Kashmir insist the courts are free from interference and due process is being followed.

Responding to a letter from one of Mr Rafique’s friends, who raised the case with him in his capacity as their local MP, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson said he shared concerns about the “reported appalling treatment” of Mr Rafique and promised to raise it with the UK Foreign Office.

Mr Rafique was born in Pakistani-administered Kashmir but moved to the UK as a young child. In 2005, he travelled back to Kashmir to spend time with his grandmother and eventually left his job in finance to settle permanently in the region. Control of Kashmir is split between Pakistan and India, which have fought a number of wars and smaller conflicts over the region. Both countries lay claim to Kashmir in its entirety.

Mr Rafique, however, is part of a movement calling for a completely independent, united Kashmir. His wife told the BBC he was initially attracted to the cause after realising how difficult it was for his family in Pakistani-administered Kashmir to visit their relatives in Indian-administered Kashmir. “He thought, this used be one state and it shouldn’t be divided,” she said.

But Mr Rafique’s peaceful activism attracted the attention of the authorities. Ms Rajput, his wife, told the BBC he had once previously been extrajudicially detained by the Pakistani military for three days before the British High Commission intervened. Mr Rafique’s younger sister Asma, who lives in London, told the BBC her brother was warned by intelligence agents that if he did not stop his activities, “nobody would ever hear of him or see him again”. The Pakistani military did not respond to a request to comment.

India-administered Kashmir has witnessed years of mass protests as well as a long running violent insurgency against Indian rule, with security forces accused of widespread human rights abuses. The dispute stems from the division of Pakistan and India in 1947. Tensions flared most recently when India revoked the special, more autonomous status of Kashmir last year.

Pakistani-administered Kashmir has not seen similar levels of unrest, and Pakistani officials frequently call for Kashmiris to be given the right of self-determination. Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan has described himself as a global ambassador for the Kashmiri cause, repeatedly demanding a plebiscite be held across Kashmir to decide its future in line with UN resolutions.

Mainstream political leaders, and many ordinary people in Pakistani-administered Kashmir, are supportive of the Pakistani state, which has been accused by India of backing separatist militants. However, voices in Pakistani-administered Kashmir calling for complete independence, as opposed to joining with Pakistan, have been deliberately stifled. The region’s constitution forbids any activities deemed “prejudicial or detrimental to, the ideology of the State’s accession to Pakistan”. Ms Rajput told the BBC the detention of her husband shows the “hypocrisy” of Pakistan’s position.

Raja Wasim, the press secretary to the prime minister of Pakistani-administered Kashmir, insisted laws preventing pro-independence activities were rarely actually enforced, however.

As well as publishing a blog and videos online, Mr Rafique spent years conducting a survey of public opinion in Pakistani-administered Kashmir, canvassing, he said, the views of 10,000 inhabitants of the region. According to his findings, 73% of respondents identified primarily as Kashmiri rather than Pakistani.

A study by the international affairs think tank Chatham House in 2010 found that 44% of residents in Pakistani Administered Kashmir favoured independence, whilst 50% wanted to join Pakistan.

The results of Mr Rafique’s survey were published in a local newspaper in 2017, but in a sign of how sensitive the issue is authorities ordered the newspaper to be shut down in response.

This August, Mr Rafique began a hunger strike in protest at the placing of Pakistan’s national flag in the centre of the city of Dadyal in Pakistani-administered Kashmir. The region has its own flag and its own parliament, with a degree of autonomy. In a message sent from jail, seen by the BBC, Mr Rafique said he “considered it my public duty to peacefully resist” and take down the flag when officials failed to do so.

A fellow activist filmed Mr Rafique scaling the gate of a square that local residents have named in honour of a Kashmiri separatist leader who was executed by India in 1984. The video shows Mr Rafique removing a Pakistani flag, before being hauled away by police. The footage was picked up from social media by Indian TV channels, a development that was specifically mentioned in the case registered against him and which likely angered Pakistani officials. His wife, however, told the BBC Mr Rafique opposed both Pakistani and Indian policies in Kashmir.

In his message from jail, Mr Rafique described being “punched” and “beaten with sticks” during his arrest and subsequent interrogation. His wife alleged he had at times been kept in isolation in a cell normally reserved for those accused of crimes warranting the death penalty, until the British High Commission in Islamabad intervened. She said she believed his life was in danger as a result of his hunger strike.

Mr Rafique’s family in Luton have been calling on the British Foreign Office to step up efforts to secure his release. His sister Asma Rafique told the BBC that while the British High Commission had been in contact with them, they felt “disappointed” with the level of support they had received and the slow pace of progress. “I feel as is if everything is falling upon deaf ears,” Ms Rafique said.

In a statement the UK Foreign Office said it was offering “offering assistance to a British-Pakistani dual national” and its staff were “in regular contact with his family, his lawyer and the Pakistani authorities”.

Ms Rafique said the ordeal had caused an “immense level of stress” for the family. “I feel as if all our concerns are falling upon deaf ears,” she said.