US President-elect Joe Biden says the international system is “coming apart at the seams”.

He’s promised to salvage America’s reputation and says he’s in a hurry. “There will be no time to lose,” he wrote in Foreign Affairs magazine earlier this year.

On his long to-do list is a pledge to rejoin the 2015 Iran nuclear deal – the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), to give it its formal title – one of the signature, if hotly debated, achievements of Donald Trump’s predecessor in the White House, Barack Obama.

Since withdrawing from the deal in May 2018, President Trump has been doing his utmost to demolish it.

But despite more than two years of Mr Trump’s policy of “maximum pressure” on Iran, the Islamic Republic has not buckled and is closer to acquiring the technology needed for a nuclear weapon than it was when the US started to turn the screws.

Will Joe Biden, who takes office in January, return to the status quo ante? Given the passage of time and divided state of American politics, can he?

“The strategy is very, very clear,” says Aniseh Bassiri Tabrizi, an Iran expert at London’s Royal United Services Institute (Rusi). “But it won’t be easy.”

‘No going back’

It’s fair to say there are considerable challenges.

The complex web of US sanctions imposed over the past two years gives Mr Biden plenty of possible leverage, should he choose to use it. So far he’s talked only in terms of Iran upholding its existing JCPOA obligations.

“Tehran must return to strict compliance,” he wrote in January. But that’s already a challenge. Following Donald Trump’s exit from the JCPOA, Iran began to row back on its own commitments.

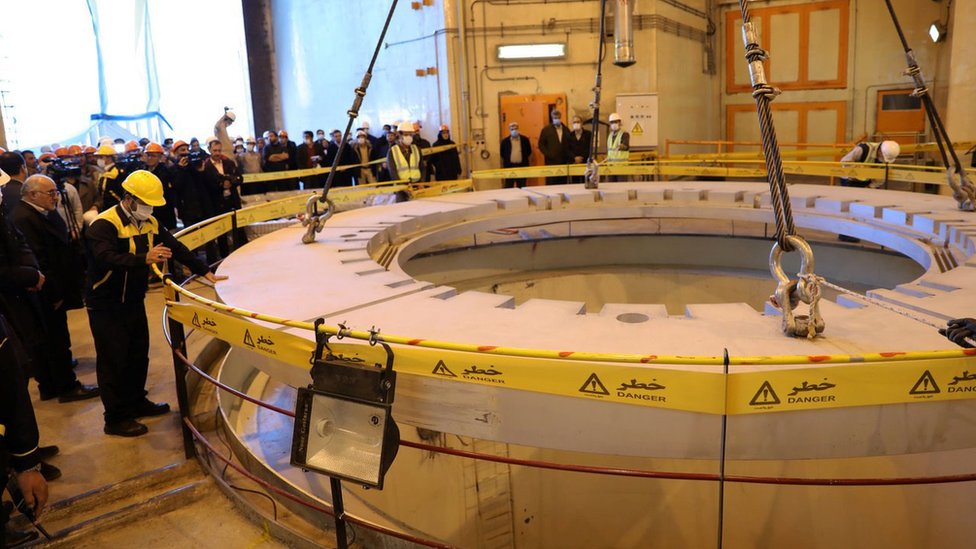

In its last quarterly report, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) said Iran had stockpiled about 12 times the amount of low-enriched uranium permitted under the JCPOA.

It had also started enriching uranium to higher purity than the 3.67% allowed under the deal.

Low-enriched uranium is used for many civilian nuclear-related purposes – but at its highest state of purification (which Iran is nowhere near, nor known to be pursuing) it can be used in a nuclear bomb, hence the concern.

While these are probably relatively straightforward issues to deal with – Iranian officials have repeatedly said their moves towards non-compliance are “reversible” – advances in Iranian research and development can’t simply be erased.

“We cannot go backwards,” says Ali Asghar Soltanieh, Iran’s former ambassador to the IAEA. “We are now reaching from point A to point B, and this is where we are now.”

Political pressure

But Iran, which has weathered the Trump storm, has its own demands. Officials say the removal of sanctions won’t be enough. Iran expects to be compensated for two-and-a-half years of crippling economic damage.

With Iran’s own presidential elections looming in June next year, reformist and hardline camps are jockeying for position.

President Hassan Rouhani’s ratings have fallen as Iran’s economic situation has worsened. Will Joe Biden feel the need to boost Mr Rouhani’s chances by starting to ease sanctions?

Nasser Hadian-Jazy, a professor of political science at the University of Tehran, says Joe Biden should make his intentions clear before taking office.

“A public message that he’s going to go back to the JCPOA, unconditionally, in a speedy way,” he says. “That’s good enough.”

Failure to do this, he adds, could allow “spoilers” in Iran, the US and the region to wreck chances of rapprochement.

But Mr Biden’s own room for manoeuvre may be limited. Support for the JCPOA in the US has largely broken along partisan lines, with Republicans mostly opposed.

The results of Georgia’s two Senate run-offs in January will determine the balance of power in Washington and, possibly, the incoming administration’s freedom to act.

New alliances

Of course, the JCPOA was never a bilateral affair. Its other international sponsors – Russia, China, France, the UK and Germany, plus the European Union – are all, in one way or another, invested in its future.

The European sponsors, in particular, are anxious to see Washington once more committed to the deal’s success. The UK, France and Germany (the “E3”) have tried to keep the deal alive during the Trump years and could now play a role in negotiating the terms of Washington’s return.

But in London, Paris and Berlin, there’s a recognition that the world has moved on and that a simple return to the original deal is unlikely.

“Even the E3 are now increasingly talking about a follow-on agreement to the JCPOA,” says Aniseh Bassiri Tabrizi of Rusi.

Any such deal, she says, would aim to cover Iran’s regional activities and development of ballistic missiles, as well as limiting Iran’s nuclear activities as the JCPOA’s provisions begin to expire.

The fact that some of the regional states which opposed the JCPOA – Israel, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain – have recently signed normalisation agreements sponsored and heavily promoted by the Trump administration will make their interests much harder to ignore.

“If we’re going to negotiate the security of our part of the world, we should be there,” the UAE’s ambassador in Washington, Yousef al-Otaiba, told the audience at a recent seminar organised by Tel Aviv University’s Institute for National Security Studies.

The ambassador’s determination was echoed by his Israeli interlocutor, the institute’s director, Amos Yadlin. “Israel also wants to be at the table,” Mr Yadlin said, “with our allies in the Middle East.”

For his part, Saudi Arabia’s King Salman has called for “a decisive stance from the international community against Iran”.

Reviving the JCPOA while simultaneously accommodating the views and interests of those who fear or despise it will represent a fiendishly complicated Rubik’s cube of diplomacy for Joe Biden. And let’s not forget: his predecessor isn’t done yet.

US media also reported that Mr Trump last week asked senior advisers about options for attacking an Iranian nuclear site, only to be dissuaded.

But, in defiance of the traditional norms associated with “lame duck” administrations, he is still bearing down on Iran, introducing new sanctions since his election defeat and threatening to impose even more.

Whatever he ends up doing between now and the end of January, the intention seems clear: to make it as difficult as possible for Joe Biden to undo the damage.