‘We satiate the hungry, we heal the dying, and we are the ones who shield the weak’. It plagues us and it plagues us deep. The deleterious complacence that we work hard to sustain them; we sweat and bleed – the blue elixir – that earthlings in the poorer half of the world live on. We – the development enthusiasts – are a bunch of cocksure men (and ‘hensure’ women) who presume that their exalted profession excepts them from all kinds of answerability. The sensitivity of our profession though is such that we infect when we err and kill when we blunder.

Disturbed by an unnerving dream, or supplied with some super-classified evidence, the interior minister woke up to declare Pakistan off limits to the famous NGO, Save the Children. It was banned. It was unbanned; as the nation saw Islamabad in awe. What was happening out there? Nobody knew; it was a tragic comedy of sorts.

Nevertheless, we – the development community – hardly had the moral high ground to stand tall the way we did. We did not care to probe the matter at our own end? No. We launched into a chastening campaign against the government, and such highhandedness plagues us deep – in Bangladesh, in Cambodia, in Pakistan!

The Haiti earthquake episode, where the American Red Cross was merely able to build 6 homes after having raised half a billion dollars is one unfortunate example.

Our liberal approach to self-evaluation has left us vulnerable to all kinds of threats from the inside and out. We know our management of aid is far from enviable. The sheer spread of our private donors around the globe makes following the trail of their feel-good donations impossible for them. Naturally, they tend to sit back and relax with a light conscience heaping us with loads of trust. What do we do in turn? We mark our achievements and sweep our shortcomings under the carpet. The Haiti earthquake episode, where the American Red Cross was merely able to build 6 homes after having raised half a billion dollars is one unfortunate example.

Analyzing the effectiveness of aid is further complicated by the difficulty of accounting for the ‘true cost’ of providing services a particular NGO is providing. That is, does the accounting cost reflect the true, competitive price for a similar service in the open market? Indirect costs eat away a substantial part of aid money and answering such questions can be very challenging without candid data dissemination by NGOs.

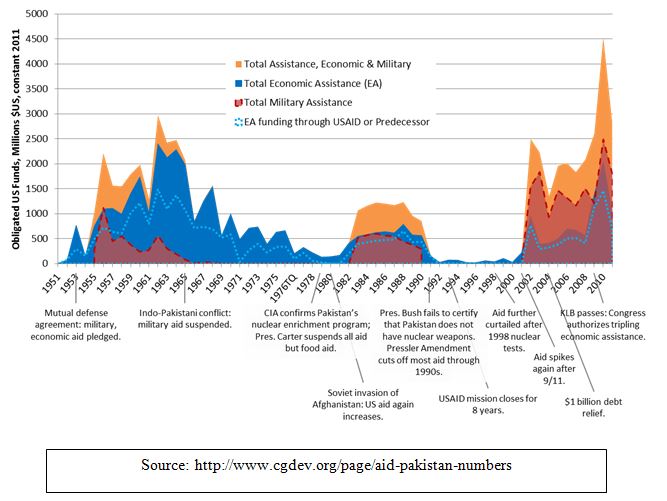

Yet a graver threat to Development, which makes even our alarming weaknesses seem rather trivial, is how the donor countries dress their obscene political interests in majestic altruistic garbs. There is no dearth of literature documenting the American influence on the World Bank and its International Development Agency’s lending. On a bilateral level, the case of sudden drop in the US aid to Pakistan as soon as the Soviet War ended and its resumption as soon as the so-called War on Terror began make textbook examples of how international aid can be politically motivated.

But there is still an even viler case of the deployment of international aid to achieve political ends: the use of NGOs for ‘promoting democracy’ and even ‘information-sharing’, which to some are euphemisms for intelligence operations and spying. Emad Mekay, of the Investigative Reporting Program at UC, Berkeley traced the stream of funding for anti-Morsi activism back to American sources. These NGOs were mostly working for ‘promoting democracy.’ Ironically, their efforts resulted in a coup that ousted the freely elected president (sentenced to death later) and installed a military commander, General Sisi, in his place.

Similarly, this document on the CIA website gives an interesting account of how INGOs provide crucial information in conflict zones and the potential that lies in such cooperation. Unsurprisingly, these proposals come from a former head of the American National Intelligence Council, preoccupied with security and lacking a deeper understanding of humanitarian values and the caution that such noble missions have to go with. Save the Children has been classified by the writer as being in the group of NGOs that “have contact with foreign governments as needed for security and practical reasons…”

The government’s crackdown on NGOs is a classic example of how worse things can get. On back of Save the Children comes the threat to revoke the license of the esteemed British Council.

Of course, that does not provide even a pinch of proof to hold Save the Children responsible for its allegedly controversial activities. Save the Children is an organisation par-excellence as far as its effectiveness and transparency are concerned. But the point to be taken here is that the engagement of an NGO with donor governments risks profound defamation of development work. Its stigmatisation – even if ungrounded – casts a shadow over the genuineness of the whole development enterprise, evoking an unneeded paranoia in the private donors and recipients alike. The government’s crackdown on NGOs is a classic example of how worse things can get. On back of Save the Children comes the threat to revoke the license of the esteemed British Council.

Who is responsible for the mess? The government? Yes. But no more than us, ourselves. We the development workers need to campaign for making the development work transparent and free from political influence in all hues. For that, a good starting point is drawing a blueprint for an autonomous, apolitical, international development organization that pools all aid from public as well as the private sources and allocates it to the best-managed NGOs for the most urgent projects. All direct donations to developing countries from the rich ones, with that lofty label of ‘development’, should be barred officially. Until the formation of such a regulator, or at least credible steps in that direction, it will be only natural for NGOs to keep facing bizarre pressures – sometimes from the donor countries and sometimes from the recipients.

Very Well Written. It was lovely read